It was an uncharacteristically optimistic Friday in New Jersey: I was out for a long, leisurely road bike ride around my home, and was looking forward to the possibility of spending time on Saturday with the most amazing, brilliant person, whom I had recently met. But then things — part literally — fell apart. I had a flat 26 kilometres into the planned 120 kilometres, and my cheapo CO₂ regulator disintegrated into 5 pieces as I tried to inflate my new inner tube, taking a chunk of my thumbnail with it. As I rode an Uber back home desperately trying to avoid leaving my blood in someone else’s car, I learned that the person I wanted to hang out with was busy on Saturday and wasn’t going to be around for at least a week.

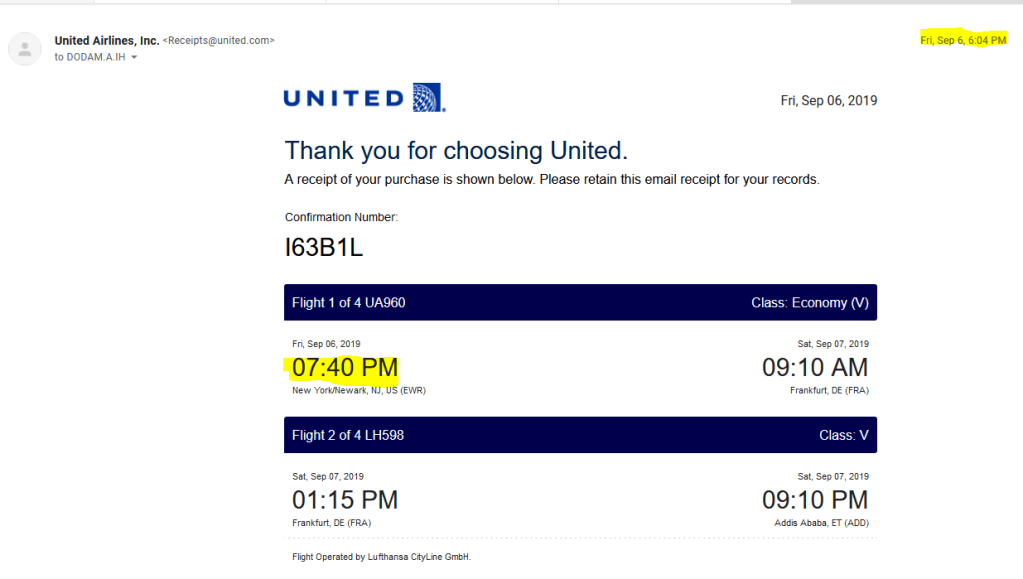

It was 4:30PM, and life had given me lemons. So, like any other reasonable person, I decided to make the biggest lemon grenade I could think of and launch it back at life: I booked (what I thought was) a 7:40PM flight for Ethiopia, quickly threw a few things that I thought I might need into my bike bag, and then called an Uber to Newark Liberty International Airport.

Remembering my first 5 kilometres

By the end of my first semester at Princeton, a few friends that I had made had independently compared me to Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye. I hadn’t read that book back then, and asked people for their opinions on whether the comparison seemed valid in their eyes — my dear father lovingly observed that Holden was “probably the only character in all of literature that is as much of a loser as you are”, while my friends were split down the middle on whether the comparison comprised an insult. What I found odd was that even back then, a couple people told me that I was “adventurous” and “spontaneous”. (Given that one of those people was my physics lab partner who had to suffer through my legendary inability at empirical experiments that would put Wolfgang Pauli to shame, I suspected that “adventurous” meant ‘unorthodox in method’ and “spontaneous” meant ‘thoughtless in application’.)

In truth, I was nothing of the sort back then — I suppose I had been living by myself for three years at that point in Canada either with a random Filipino family or in a dorm, but that was much more me running away from home (that does sound like Holden, doesn’t it?) than seeking adventure. I certainly was well-travelled for a high school student, but I’d only really done two trips by myself outside of flying back and forth between my high school dorm and Korea, one of them being Princeton Preview (which was my first missed flight due to oversleeping, no less). The other was a circumnavigation that I’d done in the summer after graduation: I flew from Korea to NYC to see someone for two days and then went on to Germany to stay with my high school friends for a month before coming home.

That’s not to say that I didn’t have the spark in me, though. I distinctly remember the first real moment when I acted on the thought ‘I just want to get out and go somewhere even though it might not make sense to most people’; it was on that first real trip by myself, in a small German town close to the Netherlands called Bocholt where my friend Philipp lived. I’d just recently experienced one of the saddest days (to then) of my life, and aided by some Weizenbier, I decided to bike off into the midnight toward the Dutch border in a thunderstorm laughing like a madman. Philipp chased after me with a smile and two bottles of beer, making me promise that I wasn’t going insane. Looking back, it’s uncannily prescient that my first true act of spontaneity in travelling should have been biking in questionable conditions to a different country long, long before I was a cyclist and much less a bikepacker.

Oh, how happy and alive I felt on that grey, pouring midsummer night almost ten years ago! How Philipp and I laughed, drenched head to toe for no good reason; how my petty troubles evanesced and dissolved into the moment; how I gazed at the moon, wondering if the people that I loved kept me in their thoughts! I am so grateful to my past self for having had the courage to start those five short kilometres, for without them I would not be here.

Spontaneity can’t be spontaneous

On the Uber ride, I purchased travel insurance and started frantically sending messages to Warmshowers hosts in Addis Ababa asking if I could stay with them for a night (my flight was due to arrive late at night) and leave my bike bag with them. (Note for non-bikepacking readers: Warmshowers is a website where you can sign up to host bikepackers / cycle tourists and provide them with assistance.) I would just do my research on the airplane and enlist some help from my best friend.

When I arrived at the airport and tried to check in, I found out that I’d actually booked tickets for a flight that left the next day rather than that evening. (I know, okay?) There was no cancellation fee, so no harm done; I just cancelled and rebooked on the spot for a flight due to leave in less than two hours, checked in, and handed over my beloved bike.

I mean, I was already at the airport….

At this point, I should explain why I felt comfortable throwing together this lemon grenade of a trip: there was a method to my seeming madness beyond it being a thinly veiled socially acceptable form of self-destruction, which is what some of my friends thought it was. (Note: I’m terribly sorry that this is going to be so long-winded for the people who are only interested in the bikepacking — please skip ahead a few paragraphs to the part where I start talking about the gear. I have to include this because it’s important for the people that I expect to meet in the future since I think this will be a crucial point in my life and a big part of me keeping this blog is a record of myself and not just me bikepacking.)

I’ve decided to delay the start of my actual tour until early November for a number of reasons, the biggest being that I wanted to enjoy the freedom that I currently have a bit longer: I do need to finish my Master’s thesis, but I’m done with the coursework; I am a single male without a family to take care of or a special person to love, appreciate, and support with every fibre of my being; I don’t have work because I’m getting ready to go on tour and have exceptionally generous and supportive parents; I’ve been living away from my family for 14 years and they don’t need anything from me; I have basically no obligations that take any sort of time other than being there for the people I care about, who are all too busy to spend time with me anyway. Right now, I can just disappear for a week or even longer without telling anyone and nobody would really care. (On that front, anyone reading this, wherever you’re in the world: if you think I sound cool and want me to join you for bikepacking in the next few weeks / might want to join me, or just want to have intense — preferably in-person — discussions, just shoot me a message! If you think I’m a dork, I’m sure you’re still a wonderful person.)

The last piece of the freedom puzzle — and perhaps the most important — was my dog, who’d been my housemate, destroyer of vacuum cleaners, support, and responsibility for the past six years, including my senior year. (He has the distinction of being the first approved therapy animal ever to live in a dorm on Princeton campus — I helped develop the policy and was the test case.) He was what anchored me to be home each night and forced me to take day trips from New Jersey to Cambridge / Boston, the only thing that kept me from absconding completely without planning. But he was now with my brother, and I was freer than I’ll ever be my entire life, without any sort of real — or rather, material — attachment to anything or anyone. As such, mentally, I was ready to do whatever captured my fancy, and much, much more so than usual, with an elevated appetite for risk. Given that the amazing person was unavailable and I’d just been cheated out of a long ride, I just wanted to do something silly and adventurous.

Choosing the type of the adventure I wanted was easy: another reason that I had decided to delay my trip was because I didn’t feel confident in my gear, setup, physical ability, and crucially, whether I could really be in the routine of bikepacking over a longer period. It may sound a bit weird coming from someone who wants to tour around the world, but my longest bikepacking trip before Ethiopia (which still wasn’t very long) was in Morocco last year, which was 5 days on the bike. I still wasn’t sure if I would really be capable of sustained efforts over anything longer, whether I would be able to survive in a different country under adverse conditions, and above everything else, how much I could enjoy myself while alone. I felt the need to test everything in a more hostile environment, notwithstanding my last trip to the Pacific Northwest. Naturally, I would go bikepacking in a foreign country without any sort of planning. And honestly, if you’re going to go to another country without planning, it really doesn’t get better than bikepacking since you don’t need to find accommodation or transportation.

Choosing the destination was also easy by a process of elimination: I wouldn’t go to South America because I was going to be there relatively soon; Southeast Asia and Central Asia was way too far for an 8 day trip including flights; Europe, Australia, or East Asia was something I could easily convince a person I might meet in the future to do with me, and also too easy. That left Africa, and I wanted to see East Africa again since my happiest memory ever came from the Rift Valley. I needed the terrain to be challenging, the history to be interesting, and the people to not speak English: Ethiopia it was.

After the idea came to me, I thought about what’s stopping me from making this trip, and there was nothing that I could think of. So I decided to do it.

Here’s the important thing though: this sort of spontaneity isn’t spontaneous. My bike and gear was ready to go because I had never unpacked it from my last trip to Seattle; I had enough energy and fitness to go bikepack since I had been preparing for my tour; I had been vaccinated for literally everything under the sun (here’s the list of every vaccine that exists) except for the flu (not the season yet), HPV (too old), pneumonia (unneeded for young people), smallpox (kinda unnecessary in 2019), and anthrax (difficult to get if not in the military). I had set everything up for this sort of trip in the course of preparing for the tour.

And even though this is extremely uncharacteristic for me, I actually do have a packing list that’s something like 150 items long and weighs 25kg without food or water, which is, admittedly, exorbitantly long and needlessly heavy, especially for a bikepacking (rather than cycle touring) setup with a lot of ultralight gear. A few people have remarked that half the things I’m carrying aren’t needed and that I should go lighter, but the extra weight is precisely what allows me to take unplanned detours, and in this case, it was what allowed me to make an entire unplanned trip. One person asked me on the Bicycle Touring & Backpacking how I knew what to pack if the trip was unplanned; the answer was that my setup lets me travel anywhere as long as it isn’t too cold.

Arriving in Addis and realising that I wouldn’t have cell or data

There was a 4-hour layover in Frankfurt, so I decided to get out of the airport and grab breakfast in the city. I’d been on the local radio years ago as a weird tourist overly knowledgeable and excited about German history and Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, and I wanted to see the city again. It was a drizzly day, and I had a breakfast buffet at a hotel; I then walked around unsuccessfully looking for a bike shop because I knew I hadn’t packed gloves before returning to the airport.

I eat a healthy balanced diet.

Meanwhile on Warmshowers, a man by the name of Juerg in Addis had generously agreed to host me for a night even though I would be arriving super late, and let me leave my luggage with him for a week. I asked him what kind of gifts I might bring them, and then had decided on various snacks for his son, which I bought in Frankfurt.

The plane finally landed in Addis Ababa, and it was at this point that I discovered something completely unexpected: Project Fi (which is Google’s cell service with unlimited data) did not work in Ethiopia. I had assumed that it would work in Ethiopia since it’s supposed to work seamlessly across over 200 countries and Ethiopia was one of the most important countries in Africa, but somehow a service that covers Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had omitted the capital country of the African Union.

This revelation was as exhilarating as it was terrifying. As any international traveller is wont to agree, the degree to which smartphones facilitate travelling — and especially last-minute travelling — simply cannot be overstated. Translators make interacting with locals easy without learning the language; travel websites render planning trivial; satellite maps ensure you’ll never be lost. And while I had expected at-best spotty cell coverage from my previous experiences in Morocco, Armenia, and Georgia, I had never been in a situation like this where I would be completely without internet. Part of me revelled in the thought though; after all, isn’t this what exploring was supposed to be about? And I certainly needed the practice.

After an interminable 2-hour wait, I finally got my arrival visa. And as per the usual, I was relieved to see that both my bike bag and my equipment bag had made it safely. There were other bike bags at the luggage claim, which I was super excited to see — I really wanted to stay back to say hi to the other cyclists, but I didn’t want to keep Juerg up any later than I had to. I grabbed some Ethiopian birrs at an ATM and took a taxi to Juerg’s place.

My tribe is here!

I’ve been on many first taxi rides in a new country, and thought I wouldn’t be surprised by anything — this really was something else though. The roads were utter chaos, there were “potholes” everywhere, and the abject poverty and lack of urban planning jumped out at me even through the late night. Oh, and I saw a man randomly carrying an AK-47 in the middle of the street. (Spoiler alert: This would not be the last time I would see a gun in Ethiopia, and I would end up having a loaded one pointed at me.)

When I arrived at Juerg’s place near midnight, he was waiting for me even though the rest of his family had gone to sleep. I did as much research as I could and came up with a rough direction of where I wanted to go that night while I had internet — I would have to go south towards Bale Mountains National Park since the weather was going to be terrible toward the north, and I didn’t really have enough time to get to Gondar or Mirabelle. I went to bed around 2AM, and then woke up at 5AM to put my bike together. I had a long day ahead of me.

Of horses, cows, and raw meat

Juerg was awake by the time I finished assembling my bike. I met his son Julian, and handed off the Haribo and the Kinder chocolates I’d brought. As I put the finishing touches on my bike, Juerg warned me about how children might throw rocks at me, and a few other things I should look out for. He also told me that people would call me “China”, because every “white” person was “China” regardless of where they were actually from. After a commemorative photo, I was off.

Juerg, Julian, and me.

Navigating the morning traffic in Addis was quite fun, but it was also the sort of thing that wouldn’t be pleasant for most people. Fortunately, I’m the weird kind of person who actually likes driving in New York City — I find it to be a pleasant challenge that stimulates my spatial awareness. To me, weaving between cars, people, trucks, minibuses, actual buses, taxis, minitaxis, cows, goats, sheep, and horses on roads that didn’t have lane markings was such a pleasant experience, and I relished the feeling of having been thrown into the chaos.

Horses.

More horses.

More “traffic.”

I stopped for my first of many coffees: Ethiopia was the birthplace of coffee, and getting good street coffee on the cheap was something that I had been looking forward to. The random coffee shop I went into did not disappoint — for less than a dollar (even though I was getting gouged as a foreigner), I had the most amazing espresso boiled over charcoal and frankincense. The locals found it amusing that I felt the need to take photos of the coffee burner.

I made another short stop to stock up on groceries: I was planning on wild camping every night, and didn’t have any real food outside some snacks and protein mixes from stripped MREs that I was carrying as emergency food. I bought some local soft cheese, sweet bread, and dates. And then it was time to find breakfast.

One of the things that I pride myself on is being adventurous with food, and no matter where I go, I am always willing to try whatever the locals eat. This is partially because I’m a huge foodie, and I deeply cherish the dynamic range that food from travelling brings to my life: I’m just as at home eating 12 course meals at restaurants with multiple Michelin stars in Manhattan as I am trying raw meat in Ethiopia on a bike. (I literally cannot think of anything that I wouldn’t try at least once in terms of food, in much the same way I cannot imagine saying “I don’t want to discuss this right now” about a topic.)

I went into an eatery and asked the shopkeeper what he had, and he replied “meat”, which sounded good to me. He then asked me “raw or roasted”, so I responded “raw” — he seemed taken aback, gave me a puzzled look, and asked me again to confirm. But given that steak tartare is one of my favourite dishes, I wasn’t going to pass up a chance to try the Ethiopian version (called kitfo, served with various spices and butter) of it. My meat came out with the injera (fermented flatbread which is the staple of Ethiopian diet), and I dug in. I loved every bite of it — it was so juicy and full of flavour.

Another cup of coffee later, I started making my way through some back alleys of Addis on a mission to find the main road leading south. After a photo stop by a market that was going on, I had found my way successfully.

Being “China” on a machina, and the rocks thrown

The main “highway” greeted me with questionable conditions. It was the tail end of the rainy season in Ethiopia, and the roads — especially the sections that weren’t paved — had heavy flooding. I initially tried to be as courteous to cars as I can be and ride on the shoulder, but I quickly changed my mind after an encounter with a muddy pothole covered my legs and my bike in mud.

The rest of the day was going to be just riding on this one road until the night, when I would find a good place to camp off the side of the road. I picked up some kerosene for cooking from a gas station, and got into the groove of pedalling as the scenery became more rural.

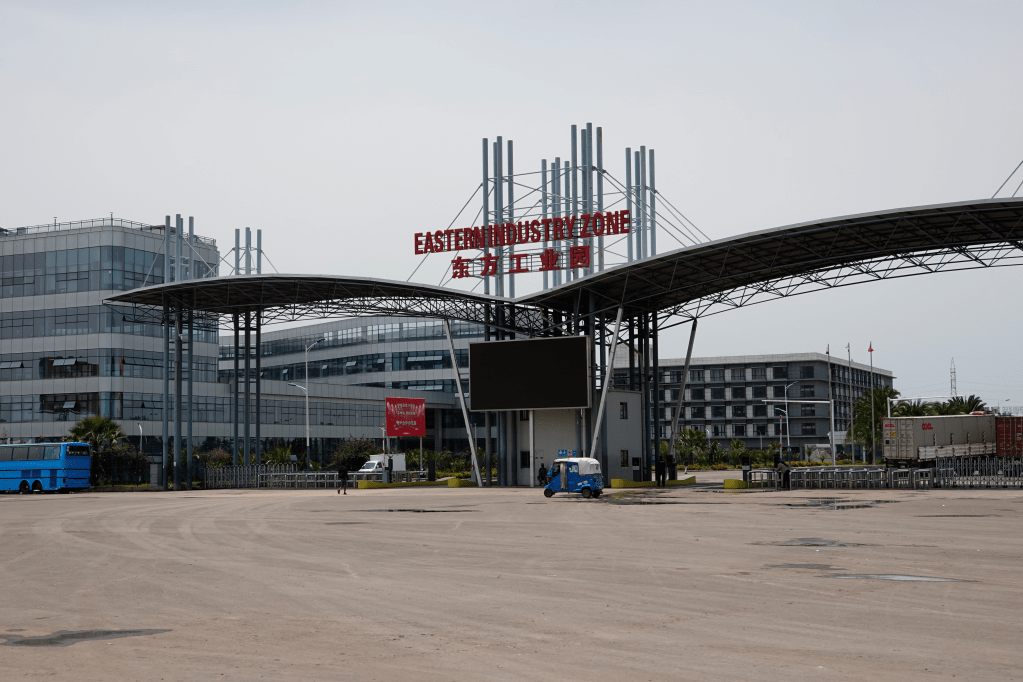

As I rode past, people yelled “farangi” or “China” at me to get my attention. Both were synedoches that referred to foreigners; the term farangi entered Amharic via Arabic as a corruption of “Franks” from the days of the crusade, whereas the term China was due to the recent heavy Chinese influence. And the Chinese influence was unmistakable: I would see random Chinese factories and signs in Chinese everywhere, and every time I passed by a sign advertising an infrastructure project, the sign was sure to be accompanied by a Chinese version.

As a Korean, I was used to being misidentified as being Chinese, and then Japanese. This was on a different level, though, since literally every foreigner was “China”. The last time I had been in this part of the world ten years ago, I was told that every foreigner was “America” — oh, how the times have changed!

Anyway, there were two main reasons why people wanted my attention: the first was just because I was interesting as a foreigner on a bicycle in rural Ethiopia and they wanted to see my face, and the second was because they wanted to ask for money. I understood that both were entirely natural things to do — I’d never felt so much like a literal alien as much as I was feeling, clad in lycra on an Italian carbon gravel superbike with aerobars casually passing through rural Ethiopia, speeding past overloaded donkey-carts. And in fairness, it would take an average person in rural Ethiopia twenty five years of saving every penny earned to buy my bike, and closer to a lifetime to buy everything I was carrying. (I am planning on doing a post on ethics of travelling at some point, so keep an eye out for that.)

The calls were initially flattering since I definitely enjoyed being the centre of attention, but even I eventually started getting tired of the incessant shouts of “faranji” and “China”. And my enthusiasm for interactions with locals waned even further as every time I would stop to take a photo, ten people would run up to me and ask for money. (They didn’t speak English, but pronounced the words “give me money” with surprising fluency.) On occasions, the children (who were shepherding by the side of the road) would throw rocks at me to get my attention, or threaten me with a whip. And each time I would pass a village, a kid would notice me and yell “FARANJI!”, after which every kid in the town — sometimes numbering in the twenties — would come out and run after my bike, sometimes actually trying to grab things off my bike.

I had been warned about the rock throwing by Juerg and also my best friend (who did some research for me while I was flying), but I hadn’t made a big deal of it, partially because it defied reason to think that there would exist so many people who would throw rocks at cyclists for fun. Eventually, every time I saw a kid grabbing a rock, I would just bring out one of my water bottles from the feed bag and made a motion indicating that I was going to hit him with it, which was enough to deter most of them; unfortunately, it didn’t deter kids from throwing the rocks at the back of my head after I’d passed, and I had a really tough time suppressing the urge to just throw my bike to the side of the road, run back to the kid and beat him to a pulp. And it wasn’t just rocks, either; I also had water bottles and jerry cans full of ‘drinking’ water that had just been taken from the ditches off the side of the road where the cattle were grazing thrown at me.

All of this meant that I was determined not to give out any money, at least in the context of people coming up to ask me for some — I’d rather donate to the village elder, a school, or an NGO, but there was no way that I was going to encourage begging. The only time I gave out money was to the kid who took the photo below for me, who helped me pick up $70 in cash that I’d dropped that had been strewn by the wind. As far as I could tell, he hadn’t taken a single cent of that money, and I really wanted to reward his honesty.

This isn’t to say that all of my interactions with the locals were bad — so many people gave me thumbs up or huge smiles as I passed, and there were kids who came to the road to give me high fives. And truth be told, most of the kids were just excited to see something new and different that they didn’t get to see every day, which was something that I of all people appreciated, given that childlike wonder is something I value so highly. It was such a wonderful feeling to know that me smiling and waving back at them had just made the day for some children, a fleeting moment of genuine connection between two human beings from two different worlds. Being a china on a machina (one of the Amharic / Oromo words for ‘bicycle’) was, if nothing else, a thoroughly unique experience.

A near death experience

I had just passed the headquarters of the Ethiopian Air Force after passing through yet another small town. The road was narrow, so I got off the pavement and onto the gravel shoulder to let the cars pass. As I debated whether I wanted to try and get back on the pavement or whether it would be too dangerous, I did a double-take and hit the pavement at a shallow angle. (Yes, I know that I claimed in my last post that I don’t fall often….)

As I fell toward the road, I knew that I wouldn’t be seriously hurt since the fall was at such a slow speed. At the same time, though, I saw a minibus from the other side of the road crossing toward my side of the road to pass another minibus. It was headed directly toward me. The minibus swerved precariously right after making the pass, missing my head with less than 30 cm to spare.

Having previously been intensely suicidal, I had very much processed and accepted the possibility of my own death — in fact, that acceptance was one of the things that freed me to make last minute trips like this. This wasn’t a big deal to me given that it was something that could have happened anywhere, so I dusted myself off and kept on going — I still had some ways to go.

One of the many lakes I passed.

I stopped for a late lunch, where I dressed my wound from the fall earlier, and tried some tips (roasted meat) as well as the local birra (beer). The shopkeepers looked at me in interest as I checked my GoPro and filled my Camelbak — also, my waitress really wanted to take a photo with me for some reason. After a few minutes befriending the cute goat in the back of the restaurant, I started riding again.

Finding a campsite

By the time that 7PM rolled around with the sunset, I had been riding for 8 hours, was horrendously sunburnt because of the altitude, and had covered slightly more than 165km. As I stopped at a hotel for coffee, I wondered if I was ever going to find a suitable place to camp: the road was busy, and it seemed that Ethiopians were very, very okay with walking around after dark in the middle of nowhere. There was a house every few hundred metres along the road, and there was nowhere that wasn’t someone’s farm where I could reasonably camp. Even though it didn’t seem likely that I would find a good place, I decided to keep on going.

By 11PM, I had done 205km, and had just decided to stay in a hotel if it came to that because I hadn’t seen any good options. Given the amount and type of attention I had received during the day, I certainly did not want to camp where I might be visible to other people — rural Ethiopia was surprisingly densely populated. I planned to stay at a lakeside “resort”, but when I saw the sign for it my heart jumped with joy: the sign said “campsites”. Even though stealth camping was my preferred accommodation, camping at a campsite still beat staying at a hotel by a mile in my book.

I turned onto the road to the campsite, and immediately realised that getting to the said campsite was going to be nontrivial because the dirt roads were flooded. I was able to continue on the grass for a bit, but then there came a point where I had to choose between carrying my bike through a foot of mud or stopping. I looked around: this seemed isolated enough, and as long as I got up reasonably early, I doubted that anyone would bother me. So I carried my bike behind some thorny bushes, and made camp by an anthill bigger than myself.

I woke up to the most stunning chorus of birdsongs the next morning. There were so many different birds, but unfortunately I was only able to snap one great photo of the superb starling.

Probably one of the best photos I’ve taken even if it’s slightly out of focus.

As I made hot tea and ate a breakfast of sour cheese and bread, I couldn’t help but smile: 48 hours ago, I had no idea that I would be anywhere but home, but here I was, camping by the side of a road in rural Ethiopia, seeing the sun rise to a magnificent chorale of nature. What splendid thing is spontaneity! This was the life, even though I had 2,000m of climbing to do today.

continued in part 2… But, I’m actually in Madagascar making another unplanned trip (my bike got lost in France on the way here, which is why I have time to write), so it might be a while. Sorry!

ERRATA:

(and assorted notes that are not errata)

– You should go tubeless. Even if it means setting up at the airport after you land. More compliance, less weight, less rolling resistance, more flat resistance. And you should carry a pump, not a giddanged regulator + CO2 ice-grenade.

– I agree cycling is uniquely conducive to spontaneous trips, especially the sort to which you seem to be attracted. It’s rare that we see someone with as much flexibility, time, fitness, disposable income and generally wackiness to bike around in Ethiopia on a whim.

– Regarding the kitchen sink approach to packing: Have you ever thought about the “unplanned detours” you will be *unable* to take because of the stellar mass that you lug around all the time? One form of preparation is bringing everything you could possibly need, but another is taking an ultracritical look at what you could leave behind, and just make do. Craftiness doesn’t weigh anything.

– notwithstanding the above comment: You didn’t pack GLOVES?

– The pictures are considerably better in this post.

– “Exhausted and Surprised Cyclist with Almost No Upper Body Strength Gets Ass Handed to Him by Comparatively Jacked Ethiopian 6-year-old That He Wanted to ‘Beat To A Pulp’”.

– You come close to dying at an alarming frequency. I guess this is a result of you doing a “most dangerous first” approach to touring the world. If you mingle with cars, you’re gonna get hit. Something about sleeping next to an anthill bigger than you is setting off alarm bells in my head too.

– As an American, I get FOMO when I see Chinese development and infrastructure in East Africa. With Belt and Road they’ll pay for whatever you want as long as you let them park their submarines there. (I mean, we used to pay for whatever people wanted as long as they would let us park our planes there – those were the good old days)

– Not that you’re looking for suggestions, but Oman. You should do Oman.

– Also, Mongolia. No pavement, no problem.

– Maybe I’m a bad and untrusting person, but I’m a little surprised you haven’t had your stuff stolen yet? Either at gunpoint, knife-point or just in the dead of night. Thieves in urban America will hop a fence to steal a two-thirds empty bottle of Mountain Dew, and I can only imagine what they’d do for a bike worth 25 years’ salary.

– Were I to accompany you on a trip like this in a foreign land, I would attempt to procure a bicycle locally. I bet the 3Ts are all made in that Chinese factory you passed anyway…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nate:

– I only carry a CO2 inflator on my road bike because using a mini-pump to get a tyre up to 100 psi is very unfun, even with high-volume pumps. Obviously I’m carrying a regular mini-pump on the bikepacking bike. I know I can go tubeless, but the sealant is going to make a mess if something happens in transit and I don’t want to have to deal with the hassle of setting it up every time I go somewhere.

– I actually want you to rank ‘flexibility, time, fitness, disposable income and general wackiness’ in the order of most likely to least likely 😛

– Craftiness doesn’t weigh anything, but you know what craftiness doesn’t solve? Having your rear derailleur hangar break. After what happened in Morocco, I’m not going anywhere without spares for the things that might not be easily replaceable. I do think there’s a strong argument to be made for not bringing as much in terms of electronics, but unless I’m touring in Switzerland or something, I’m going to want to carry cooking gear. And like I said, I ended up using everything except for spares that I was carrying on this trip. The gloves thing was because I’d mistakenly left one side in the bike bag while unpacking and hadn’t realised it until I got to Ethiopia.

– Travels like this are going to involve some level of coming close to dying. I’m very much okay with that, and believe or not I do try to minimise unnecessary risks.

– China is also taking over Madagascar. This country is a bit more of an interesting case because Korea tried to take over it in 2008 and that caused a revolution, but I’ll write about that when I get home.

– I actually haven’t had anything stolen for me ever in all my time travelling — granted, I’m a generally super-trusting person, but I guess I could have just gotten lucky. Some locals did tell me that I shouldn’t leave my bike unattended like I was — then again, I doubt that they knew how much a bike could cost. Most non-cyclists see a $2,000 entry-level bike and think that’s expensive.

– Yeah, but then I have to haggle for a steel clunker, and who wants to do that? I think it makes more sense for a motorcycle, but it’s easier for me to just ship a bike even if I have to spend an hour setting it up and figure out where I’m storing my bike bag.

LikeLike

(numbering)

1. Tubeless is a *slight* hassle at the airport, near civilization, which is likely to save you from multiple serious hassles in the middle of nowhere. Minimax.

2. No.

3. Craftiness converts you to a single speed to get you to the next town (or even through the whole trip). Many bike shops have derailleur hanger de-benders. Derailleur hangers are the least of your excess mass, however.

4. Don’t die.

5. Looking forward to it.

6. yas

7. Idk, depends on riding and route. Riding different bikes is fun, but I wouldn’t want to go 200mi in a day with an annoying squeak.

LikeLike